General characteristics and key aspects:

- There is a great variety of gastroenteritis in small domestic animals, and it is not always possible to determine the cause of the condition. Minimum set of tests: TCA, total protein, blood glucose, acid-base and electrolyte composition of the blood.

- Clinical signs of acute gastroenteritis typically include vomiting, diarrhea, and partial or complete refusal to feed.

- Findings on physical examination are usually nonspecific: abdominal pain, dehydration, hypovolemia.

- If the cause of the disease is unknown, symptomatic therapy is prescribed. The prognosis for most cats and dogs with gastroenteritis is excellent.

First aid

Diarrhea in a kitten: what to do and how to treat it at home

As soon as your cat develops diarrhea mixed with mucus and blood, you must immediately stop giving her food. The animal must drink a lot of water. Self-prescribing medications is prohibited. You need to collect stool and take it for analysis.

In any case, if a kitten is diarrhea with blood, then it is necessary to seek help from a specialist as soon as possible. The faster your pet receives qualified care, the greater his chances of a full recovery.

Introduction

Gastroenteritis of dogs and cats

– a rather broad term meaning the presence of an inflammatory process in the stomach and intestines. It is a common cause of acute vomiting, anorexia and diarrhea, but it is worth understanding that pancreatitis, hepatitis, and intestinal obstruction can occur with similar symptoms. There are many reasons for inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, for example, changes in diet, infectious organisms, toxins, disorders of the immune system, metabolic disorders. A history and physical examination can sometimes reveal why the inflammation started, but in most cases a specific cause is never found. Often, for complete disappearance of symptoms, symptomatic therapy, including infusion support, diet, antiemetics and gastroprotectors, is sufficient. However, in some cases, rapid decompensation may occur, usually secondary to hypovolemia, fluid loss, and thyroid hormone imbalance.

Causes and symptoms of the disease

Why is it possible for a cat to become infected with the coronary gastroenteritis virus? There are several causes and methods of infection. How is the disease transmitted?

Transfer methods:

- Oral or nasal route. The virus enters the animal's body by eating contaminated feces or by inhaling particles from trays. Even a small amount of litter from a sick cat is enough to infect other cats.

- Kittens become infected during the transition from mother's milk to another diet. While the mother feeds the kitten, the baby develops specific antibodies that protect it from various diseases. Later, the kitten’s weak immune system is not yet able to resist gastroenteritis, which becomes the cause of infection.

- A person is not able to infect a cat; the virus is not transmitted to people from sick individuals. Infection is possible from clothing or hands stained with feces.

Gastroenteritis, not caused by viruses, develops for various reasons - overeating, poisoning, allergic reactions and other pathological processes in the digestive system.

An attentive owner always monitors the condition of the pet. The symptoms of any gastroenteritis manifest themselves quite intensely, it is impossible not to notice them.

Signs:

- Decreased appetite or refusal to eat;

- Vomiting, severe diarrhea;

- Lethargic, apathetic state;

- Increased body temperature;

- When trying to eat, the animal attempts to vomit, but without vomiting;

- The abdomen is swollen, tense, painful when palpated;

- The mucous membranes are pale, with liver damage they have an icteric tint;

With the development of gastroenteritis, damage to the nerve endings is possible, the cat experiences convulsions and paralysis.

Anatomy and physiology

The stomach is a section of the gastrointestinal tract between the esophagus and the small intestine, which serves as a storage reservoir for food, and also grinds and mixes food here, which then enters the small intestine. The stomach consists of muscle layers, areas of glandular tissue and mucous membrane. With the help of muscle movements, the stomach grinds food and pushes it through the pyloric sphincter into the small intestine. The glandular areas are no less important: the parietal cells secrete hydrochloric acid, the main cells secrete pepsinogen, and the mucus-forming cells also secrete bicarbonate. Due to the barrier function of the gastric mucosa, hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes are retained in the lumen of the stomach, which prevents the loss of plasma components into the stomach. Once the food in the stomach is sufficiently crushed, it moves through the pyloric sphincter into the small intestine, the beginning of which is called the duodenum.

The small intestine of cats and dogs is divided into the duodenum, jejunum and ileum. The mucous membrane of the small intestine performs both secretory and absorption functions and consists of a monolayer of cells - enterocytes. The mucous membrane of the small intestine along its entire length forms finger-like villi that protrude into the intestinal lumen and increase its working surface. Microvilli form a “brush border”, which further increases the surface area for better digestion and absorption of nutrients.

Brush border enzymes break down larger molecules into smaller ones that are more easily absorbed. Absorption usually occurs through special transport mechanisms or pinocytosis. Epithelial cells are also involved in the absorption and secretion of water and electrolytes. Enterocytes are tightly connected to each other to limit absorption between cells and prevent the reverse flow of nutrients - from the interstitium into the intestinal lumen. The lifespan of enterocytes ranges from 2 to 5 days; they start from the crypts (the base of the villi) and migrate towards the intestinal lumen. A healthy, intact mucous membrane plays a large role in maintaining the integrity of the intestines. Any inflammation that disrupts the integrity of the mucosa can lead to serious intestinal disease. It is important to remember that the gastrointestinal tract absorbs 99% of the water entering it, therefore, any disturbances in the functioning of the gastrointestinal tract can lead to serious disorders of the water and electrolyte balance of the body.

Prevention of influenza, ARVI and coronavirus

There are a number of measures to prevent infection. Protection against influenza, coronavirus and ARVI consists of following the following recommendations:

- Avoid large crowds of people.

- In public places, keep at least a meter distance from others.

- Use medical masks and respirators.

- Wash your hands thoroughly with soap and use antiseptic gels and sprays.

- Do not touch your face with dirty hands.

- Ventilate the room, regularly do wet cleaning and humidify the air.

- Drink plenty of fluids.

- Strengthen the body's defense system with the help of herbal and synthetic immunostimulants.

History and clinical signs of inflammation of the intestines and stomach in dogs

A carefully collected anamnesis for symptoms of gastroenteritis in dogs and cats

– the basis for determining the cause of intestinal inflammation. It is necessary to ask what the patient usually eats, whether his diet has changed recently, whether he has recently had access to unusual food, foreign bodies, garbage, or toxins. It is also necessary to find out whether the patient interacted with other animals, and if so, whether these animals had similar symptoms or a history of such. In addition, when collecting anamnesis, find out the patient's vaccination status, history of deworming and use of medications.

Clinical signs of gastroenteritis

of different etiologies are similar and depend little on the cause of the disease. Diarrhea, vomiting, and anorexia are the most common symptoms, and different combinations of these signs may be more suggestive of one cause than another. Severe inflammation or ulceration of the mucosa can lead to hematemesis or melena.

Physical examination usually does not help determine the cause of the disease. You may find the patient has varying degrees of dehydration and abdominal pain. In severe cases, with parvovirus enteritis or HGE, the patient may show signs of hypovolemia and shock secondary to fluid loss and impaired blood circulation.

Prevention

To prevent the development of coronavirus gastroenteritis in a cat, veterinarians recommend:

- Try to ensure that your pet communicates less with strangers, especially street relatives.

- Wash your hands after contact with other people's animals.

- When breeding an animal, make sure that the partner chosen for it is healthy.

- The cat's feeder and water bowl should be located away from the litter tray.

- It is advisable to use clumping mixtures that produce little dust as filler.

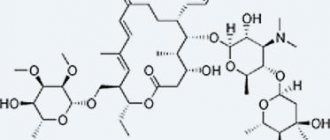

There is no vaccine that can provide a 100% guarantee of protecting cats from infection with coronavirus. According to veterinarians, the intranasal vaccine Primucell works well. It is produced by the American pharmaceutical company Pfizer. The drug is made on the basis of a weakened strain of FCoV and FIPV; its action causes the cat’s body to produce a limited amount of antibodies against coronavirus.

Etiology of inflammation of the stomach and intestines in cats and dogs

Infectious gastroenteritis in small domestic animals

The gastrointestinal tract is affected by a lot of infectious agents. Viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi can lead to gastroenteritis of varying severity. The table presents possible infectious causes of gastroenteritis, but only the most common ones are described in the text.

Infectious causes of gastroenteritis in dogs and cats

Bacteria:

- Campylobacter spp.

- Clostridium spp.

- Escherichia coli

- Salmonella spp.

- Helicobacter spp.

Viruses:

- Parvovirus

- Rotavirus

- Intestinal coronavirus - coronavirus gastroenteritis in cats

- Feline infectious peritonitis

- Canine distemper virus

- Coronavirus gastroenteritis in dogs

- Feline leukemia virus

- Feline immunodeficiency virus

Fungi, Algae and Oomycetes:

- Histoplasmosis

- Protothecosis

- Pythiosis

Parasites:

- Roundworms (Toxocara canis, Toxocara cati, Toxascaris leonina)

- Nematodes (hookworm, uncinariasis, strongyloidiasis)

- Whipworms

- Coccidia (isospores, toxoplasma, cryptosporidium)

- Giardia

- Trichomonas

- Intestinal balantidia

Rickettsia:

- Neorickettsia helminthoeca

Viral enteritis of dogs and cats

One of the most common infectious diseases in dogs is parvovirus enteritis (CPV-2), which can lead to severe enteritis, vomiting, hemorrhagic diarrhea, and shock (Chapter 112). Also, coronavirus and rotavirus can lead to severe inflammation of the intestines, however, since these viruses affect only the upper part of the villi, the inflammation rarely reaches such proportions as with parvovirus enteritis, which affects the crypts. Thus, coronavirus gastroenteritis in cats is not uncommon. Panleukopenia, also caused by parvovirus, leads to severe gastroenteritis in cats.

Bacterial enteritis of cats and dogs

Bacteria most often causing acute gastroenteritis in cats and dogs

: clostridia, salmonella, campylobacter, Helicobacter, enterotoxigenic E. Coli. However, it is currently considered controversial that some of these microorganisms can lead to clinically significant enteritis. So far, the question of the role of clostridia, campylobacter, and Helicobacter is considered open.

What can trigger the disease?

Gastroenteritis often occurs against the background of an existing disease, and sometimes it is caused by negative external factors.

Diseases that provoke gastroenteritis:

- Meningitis.

- Pneumonia.

- Oncology and benign tumors.

- Coronavirus infection.

- Poisoning.

- Diseases of the pancreas.

- Addison's disease.

- Hyperthyroidism.

- Viral diseases.

- Escherichia coli.

- Salmonellosis.

- Intestinal volvulus.

- Pathological processes of the gastrointestinal tract, such as gastritis and pancreatitis.

- Intestinal obstruction.

- Liver diseases.

- Atherosclerosis.

- Heart diseases.

- Metabolic disorders.

- Worms.

External factors leading to gastroenteritis:

- Unbalanced diet.

- Lack of a stable pet feeding regimen.

- Binge eating.

- Poor-quality ready-made food that contains an excess of dyes and preservatives.

- Food allergies.

- Ingestion of a foreign body.

- Stressful situations.

- Excessive licking, leading to the formation of trichobezoars in the cat's stomach - hair balls made from ingested hair.

Infection process

Coronavirus is one of the most mysterious viruses known to science.

There are two strains of this pathogen found in cats: FIPV and FECV. The first of them causes infectious peritonitis, but the second is precisely the cause of infectious gastroenteritis.

As a rule, cats become infected by eating feces or sniffing them, and microscopic doses of the filler on which the causative agent has come into contact with the disease are sufficient for infection.

The virus persists in the external environment for quite a long time - up to a week, which makes it even more dangerous in terms of virulence.

There is no intrauterine transmission of the virus through the placenta. Moreover, as long as kittens receive antibodies from their mother cat’s milk, they do not get sick with coronavirus.

The “dangerous” age comes later - at 5-7 weeks, when passive immunity is already fading, and active immunity has not yet had time to develop. At this time, children are especially vulnerable and susceptible to infection with coronavirus.

But a particular danger to the health and life of cats is that the relatively harmless FECV, under the influence of certain, not fully studied factors, can mutate and turn into a deadly FIPV, causing infectious peritonitis, from which a lot of cats and, especially, kittens die. .

Important!

Even if the coronavirus has entered the cat’s body, this does not mean that it will certainly get sick. If the animal is healthy and has good immunity, then the coronavirus pathogen will be completely eliminated from its body. This process can take two weeks or several months.

For the cat itself, excretion of the pathogen along with feces is completely harmless, but at the same time it can infect other animals that have weaker immunity.

Is it transmitted to humans?

Both strains of feline coronavirus do not pose a danger to humans, and this applies to those with weakened immune systems, the elderly, and even newborn babies.

Therefore, if a cat in the family has contracted coronavirus gastroenteritis, one should not be afraid of infection and, especially, there is no need to euthanize or throw the animal outside for this reason.

Hemorrhagic gastroenteritis

Hemorrhagic gastroenteritis in dogs and cats

– a disease of unknown etiology. Hemorrhagic gastroenteritis typically affects young and middle-aged small breed dogs and is characterized by a subacute onset of clinical signs, rapid progression, and without appropriate treatment can lead to death. Sick animals, as a rule, did not have any complaints before. It has been suggested that the onset of the disease may be due to an abnormal immune response to bacteria, bacterial toxins, or dietary ingredients. Although C. perfringens has been isolated from the intestinal contents of animals suffering from hemorrhagic gastroenteritis, its exact role in the etiology of the disease has not yet been established.

Vomiting, depression, bloody diarrhea (often described as “raspberry jam”) and anorexia are classic symptoms of hemorrhagic gastroenteritis. Before settling on a diagnosis of hemorrhagic intestinal inflammation, rule out other causes - parvovirus, bacterial infections, parasitic diseases. Although hemoconcentration is always present, plasma protein concentration increases very little or does not increase at all. Hematocrit increases secondary to hypovolemia and splenic contraction, while losses of plasma protein in the gastrointestinal tract and redistribution of fluid from tissues into the vascular lumen explain the slight increase in total plasma protein concentration.

For this pathology, aggressive therapy is indicated, as very rapid decompensation can occur. Most of all, adequate fluid replacement is necessary. The main goals are to quickly replace the volume of fluid lost during acute diarrhea and vomiting, and then adjust the volume of fluid administered so that rehydration is gradually achieved (more on other pages of the site). It must be remembered that the intestine is a shock organ in dogs, and insufficient perfusion can lead to worsening gastroenteritis, bacterial translocation, sepsis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Due to the loss of plasma proteins into the intestine, special attention should be paid to colloid osmotic pressure and, if necessary, provide colloid support. In addition to infusion therapy, the administration of antiemetics and antibiotics may be required (if translocation is suspected). With timely and adequate treatment, the prognosis for complete recovery from hemorrhagic gastroenteritis is good.

How to care for a sick animal

If a cat is diagnosed with coronavirus gastroenteritis, the following rules must be followed:

- isolate your pet as much as possible from other animals, it is better to go to another house, if not possible, to a separate room;

- regularly sanitize the room in which the cat is located;

- purchase an additional tray for the toilet (use one, and then soak it in a solution with chlorine for a day while the other is used, alternate), it is recommended to abandon the litter for the duration of treatment;

- cover sofas and other furniture with fabrics that can be washed frequently; the carpet (if any) should be covered with linoleum or other material that can be washed and irradiated with UV rays;

- treat the cat's oral cavity with a spray with a decoction of chamomile, oak bark or sage to disinfect and restore the mucous membrane, you can use Chlorhexidine.

Dieting

The cause of gastroenteritis in dogs (less often in cats)

The animal may absorb toxins (for example, organophosphates), foreign bodies, and debris. Some toxins directly lead to GI inflammation, while foreign bodies can lead to traumatic gastroenteritis or osmotic diarrhea (due to the presence of an indigestible substance within the GI tract). Eating foods that are too fatty can lead to pancreatitis. Medications can also cause vomiting and diarrhea: antibiotics, anti-blastoma drugs, anthelmintics. Ingested garbage can become a source of bacterial toxins. Most often, a violation of the diet leads to acute vomiting, diarrhea and anorexia. Take a thorough history: Owners should know if the animal has had access to specific toxins or debris. This diagnosis, as a rule, is hypothetical and treatment is supportive (infusion therapy, antiemetics, gastroprotectors as necessary). The prognosis is good and most animals recover within 24-72 hours.

Protein-losing enteropathy (PLE)

Protein-losing enteropathy is a general diagnosis that includes gastroenteritis of any etiology resulting in excessive loss of plasma protein. The most commonly associated diseases with the term protein-losing enteropathy are: severe lymphocytic-plasmacytic, eosinophilic, granulomatous inflammatory bowel diseases, lymphangiectasia, diffuse fungal infection of the gastrointestinal tract, diffuse neoplasia, for example, lymphosarcoma. Some of the above diseases can lead to protein-losing enteropathy if the intestinal mucosa is sufficiently damaged.

Protein loss can occur due to an inflammatory process or due to a violation of the gastrointestinal barrier. Loss of proteins very often occurs due to abnormal functioning of enterocytes, as well as when the permeability of the intestinal wall between enterocytes is impaired. Clinical signs of enteropathy are often associated with chronic wasting due to lack of nutrients in the body. However, proteins such as albumin and antithrombin III, which play an important role in hemostasis processes, can also be lost through the intestine. Albumin (molecular weight 69,000 daltons) is of great importance for maintaining oncotic pressure. Loss of albumin through the gastrointestinal tract can lead to a decrease in colloid osmotic pressure, which often leads to loss of fluid from the intravascular space. Although this process usually occurs gradually, it can nevertheless lead to a significant redistribution of fluid in the patient's body, and this should be taken into account when prescribing infusion therapy. In addition to crystalloids, transfusion of colloids or human albumin may be required to prevent further fluid loss from the vascular bed. Albumin has additional positive properties - antioxidant and anti-inflammatory.

Antithrombin III plays an important role in coagulation and fibrinolysis by inactivating thrombin and other coagulation factors. Even a slight decrease in antithrombin III levels leads to a significant increase in the risk of thrombosis and thromboembolism. Patients with protein-losing enteropathy, who lose large amounts of protein, are predisposed to vascular thrombosis in the lungs, brain, and portal vein. Treatment of enteropathy often includes glucocorticoids, which also increase the risk of thromboembolism. Therefore, in such cases, the use of anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents is often justified.

Treatment of enteropathy is based on treatment of the underlying disease. Patients with diffuse neoplasia, such as lymphosarcoma, should receive chemotherapy. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease should receive anti-inflammatory therapy and a hypoallergenic diet. Lymphangiectasia can be primary or secondary, and feeding low-fat diets may be more effective than feeding hypoallergenic foods, depending on the degree of inflammation.

Diagnostics

The extent of diagnostic testing you perform on a dog presenting with symptoms of acute gastroenteritis depends on the patient's history, history of similar problems, and the patient's stability. Fecal testing for parasites and bacteria should be performed on all animals with acute gastroenteritis. In addition to Gram staining, culture studies can be performed. The result is considered definitively negative if at least three stool tests have been performed. ELISA tests are available to detect C. perfringens enterotoxins and C. difficile toxins A and B. Antigenic tests exist for both Giardia and parvovirus enteritis.

The examination should include clinical and biochemical blood tests, and a urine test. Typically, the results of these studies are within normal limits and do not in any way affect the final diagnosis. However, in some cases, for example, with HGE (when we see an increase in hematocrit with a normal amount of total protein) or in PLE (when we see a decrease in protein, albumin, globulin, cholesterol), test data can help in diagnosis. Electrolytes should be checked regularly to ensure adequate fluid resuscitation.

An X-ray of the abdominal cavity may not be informative, but may show fluid-filled intestinal loops. However, X-ray examination should always be performed if intestinal obstruction (foreign body or neoplasm) is suspected. Ultrasound is an excellent way to examine the abdominal organs, including the thickness and layering of the walls of the stomach and intestines. Unfortunately, the findings of an ultrasound examination may be nonspecific, and they should only be assessed in conjunction with data from other studies.

If you suspect protein-losing enteropathy, you need to take a biopsy of the patient's intestinal wall, which can be done in two ways. Endoscopy is a minimally invasive method for visualizing the mucous membrane of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum, as well as for taking small (1.8-2.4 mm) samples of biopsy material. The disadvantages of the method are that the material samples are too small and the inability to penetrate distal to the duodenum. It is possible, of course, to perform a colonoscopy to obtain samples from the ileum, but this procedure requires a cleansing enema as preparation, which can lead to decompensation of an unstable patient due to imbalance of fluid and electrolytes. Another way is diagnostic laparotomy. The good thing about this method is that you can take a biopsy through all layers in any part of the intestine (or take a biopsy of other abdominal organs if changes are found in them). The disadvantage of the method is its invasiveness, and in animals with reduced albumin levels, poor healing of the postoperative wound is possible. In addition, damaged walls of the stomach and intestines heal poorly.

The most common clinical signs of gastroenteritis are vomiting, diarrhea, and anorexia. These symptoms are characteristic of many diseases, so diagnosis is often made by exclusion. Differential diagnoses for animal gastroenteritis include diseases such as renal failure, liver disease, hypoadrenocorticism, diabetes mellitus complicated by ketoacidosis, vestibular syndrome or other neurological abnormalities, pancreatitis, pyometra, prostatitis and peritonitis. From primary gastrointestinal diseases, it is necessary to exclude intussusception, foreign body obstruction, infiltrative diseases (neoplasia, infections) and ischemia. These diseases must be excluded before making a diagnosis of gastroenteritis.

Treatment of gastroenteritis in dogs and cats

Gastroenteritis in cats

— treatment must be comprehensive and affect the cause, pathogenesis, and symptoms. Most gastroenteritis in cats and dogs respond well to supportive care. The aggressiveness of treatment depends on the severity of symptoms and the underlying cause of the disease. Since the most common symptoms of gastroenteritis, regardless of cause, are vomiting, diarrhea and anorexia, dehydration is a fairly common finding, and accordingly, initial therapy involves normalizing the patient's fluid balance (see other articles on our site).

Subsequent treatment can be divided into specific and symptomatic. Specific drugs are used to treat the underlying cause of the disease. In most cases, drugs that combat infectious causes of gastroenteritis are available. Parasitic infections of the gastrointestinal tract are treated with fenbendazole or other anthelmintics. Campylobacter is sensitive to erythromycin, enrofloxacin and cefoxitin, clostridium is sensitive to metronidazole and ampicillin. The choice of drug depends on many factors, including the patient's age and ability to take drugs orally. There are very few effective antiviral drugs in veterinary medicine, so diseases such as viral enteritis are treated symptomatically. Patients with PLE are treated with therapy that targets the cause of the disease, often including diet changes and anti-inflammatory drugs.

Many drugs used to treat gastroenteritis in cats and dogs are not specific. In addition to infusion therapy, a fasting diet for 24-48 hours is recommended, and feeding should begin with moist, well-digestible food. The use of gastroprotectors and antiemetics can accelerate the regeneration of enterocytes. Antibiotics are prescribed for severe gastroenteritis when the risk of bacterial translocation is high, for example in puppies with parvovirus enteritis. Antibiotic therapy should include drugs that are effective against gram-negative microorganisms and anaerobes (that is, those microorganisms whose presence in the gastrointestinal tract is most expected).

Treatment of pathology

Treatment of the disease requires an integrated approach. First of all, the cat is prescribed a diet. It is necessary to establish a feed supply.

What to feed an animal when it is sick? The scheme will be as follows:

- During the first two days, complete food rest is recommended. Then the skimmed beef broth is introduced into the diet. The cat also needs to drink decoctions of medicinal herbs - chamomile, sage, oak bark, St. John's wort.

- From the fourth day of illness, boiled eggs are allowed. Water-based porridges are introduced - oatmeal and rice - with the addition of a small amount of minced chicken or beef.

- Then you can supplement your diet with milk porridges, fermented milk products and vegetable soups.

From the tenth day, if the animal’s condition allows, it can be transferred to the usual type of food.

Drug therapy

When dehydration is diagnosed, the cat is prescribed drips of saline solutions, as well as glucose. Subcutaneous injections of drugs in the withers area are allowed - no more than 100 ml per injection.

In order to improve digestive processes, the animal is prescribed enzymes:

- pepsin;

- trypsin;

- pancreatitis;

- mezim forte.

Festal, Panzinorm and Essentiale show a good therapeutic effect.

If the cause of gastroenteritis is poisoning, then the cat is prescribed laxatives - castor oil or magnesium sulfate.

To eliminate the pain effect, you can take painkillers.

Mezim forte is used to treat gastroenteritis.

Important. If the disease is acute, then drugs from the antibiotic category must be used. Most often, it is Levomecitin or Tsifran.

When a viral infection becomes the cause of gastroenteritis, the animal is prescribed a course of immunostimulants. Interferons, immunoglobulins, etc. can be used here. The cat is required to take long-term vitamins.

Along with the prescribed medications, the animal is prescribed antiallergic drugs. They help minimize the risk of developing an allergic reaction. This can include drugs such as Diphenhydramine, Tavegil, Suprastin or Diazolin.

Good to know

- Hematemesis in dogs and cats

- What are the main causes of protein-losing enteropathy in dogs?

- Main causes of chronic colonic diarrhea in dogs and cats

- How to distinguish chronic small intestinal diarrhea from large intestinal diarrhea?

- Causes of malabsorption in dogs

- Vomiting in cats and dogs

- Causes of acute diarrhea in dogs and cats

- Canine distemper in dogs (forms, diagnosis, symptoms, treatment, therapy)

- Esophagoscopy in dogs and cats

- Protein wasting intestinal disease in dogs. Enteropathy in dogs

- Treatment of hyperlipidemia in dogs with Bezafibrate

- Vomiting, regurgitation in dogs and cats

- Small intestinal transient disorders

- Diseases of the anus and rectum in dogs and cats

- Cholangitis in cats. Identifying, diagnosing and treating cats with neutrophilic, bacterial, lymphocytic or chronic cholangitis

- Diarrhea in dogs and cats

- Canine exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

- Enteral nutrition for dogs and cats

- Protein-losing enteropathy. Protein enteropathy in dogs

- Lymphocytic cholangitis in cats

- Acute pancreatitis in dogs and cats

- Gastric volvulus in dogs

- Fat metabolism and hyperlipidemia in dogs